Software

yampex

Yet Another Matplotlib Extension, with simplified subplotting

The Python 3 package yampex makes Matplotlib easier to use, especially with subplots and annotations. You simply construct a Plotter object with the number of subplot rows and columns you want, and do a context call on it to get a version of the object that’s all set up to do your subplots. Like this:

import numpy as np

from yampex import Plotter

funcNames = ('sin', 'cos')

X = np.linspace(0, 4*np.pi, 200)

pt = Plotter(1, 2, width=7, height=5)

pt.set_title("Sin and Cosine")

pt.set_xlabel("X"); pt.set_grid()

with pt as p:

for funcName in funcNames:

if funcName == 'sin':

p.add_line(':')

p.set_ylabel("{}(X)".format(funcName))

Y = getattr(np, funcName)(X)

p(X, Y)

pt.show()

The Plotter instance pt has various methods for setting plot

modes. The example calls two of them before it makes the context call,

thus affecting all subplots that are to be produced. It calls

pt.set_xlabel("X") to make the x-axis label “X” and calls

pt.set_grid() to include a grid, for all subplots.

Then the example code does a context call on the pt object to obtain

a contextualized instance of it, p. Everything done to this

contextualized instance applies to just one subplot rather than all

subplots. So, when the example calls p.set_ylabel with a

string-formatted argument, it sets the y-axis label of just one

subplot at a time, based on the value of funcName.

The actual subplotting is done with a call to the p context object

itself (not a method of it). The first argument is the x-axis vector

X, and all arguments that follow are y-axis vectors plotted against

the x-axis vector. In the example, there’s just one y-axis vector,

Y. You can supply additional vectors to be plotted against the first

x-axis one and they will show up in different colors.1

Once the p object has been called, the context switches to the next

subplot. In the example, there are two subplots, one above the

other. The second iteration of the for loop sets the second

subplot’s y-axis label to “cos” and plots a cosine.

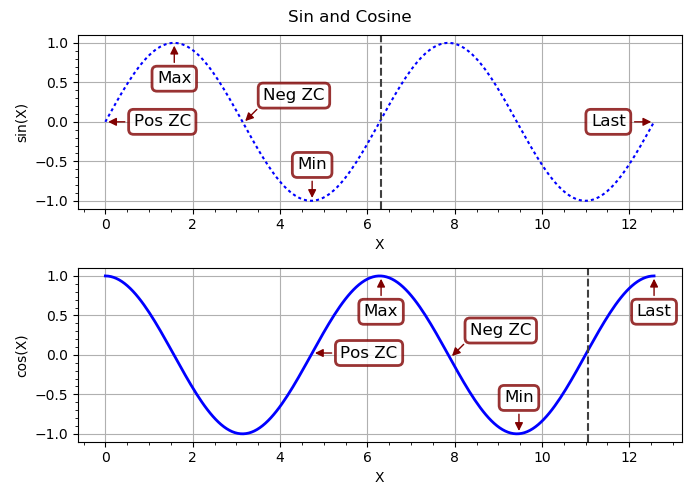

The end result of the example will look like this:

Notice that p.add_line was called for the first (top) subplot–to

give it a dotted linestyle–but not for the second. The linestyle

reverted to its solid default when the p object was called a second

time for the bottom subplot. Each call to p inside the context gets

a fresh start with the options that were set before (outside) the

context.

Annotations

Another thing that yampex can do for you is to annotate your plots

with intelligently-positioned labels. You don’t have to worry about

whether your annotation graphic will obscure part of the plot line, or

sit on top of the plot borders looking ugly and weird. And adding the

annotations is as simple as calling the add_annotation method of

your plotter object. You make the call outside the with-as context

if you want to add the annotation to all subplots, or in context to

affect just one subplot.

Let’s expand the example to add annotations to the sine and cosine curves.

import numpy as np

from yampex import Plotter

funcNames = ('sin', 'cos')

X = np.linspace(0, 4*np.pi, 200)

pt = Plotter(1, 2, width=7, height=5)

pt.set_title("Sin and Cosine")

pt.set_xlabel("X"); pt.set_grid()

pt.add_annotation(199, "Last")

with pt as p:

for funcName in funcNames:

Y = getattr(np, funcName)(X)

p.set_ylabel("{}(X)".format(funcName))

k = 0 if funcName == 'sin' else 75

for text in ("Pos ZC", "Max", "Neg ZC", "Min"):

p.add_annotation(k, text)

k += 25

p.set_axvline(k)

p(X, Y)

pt.show()

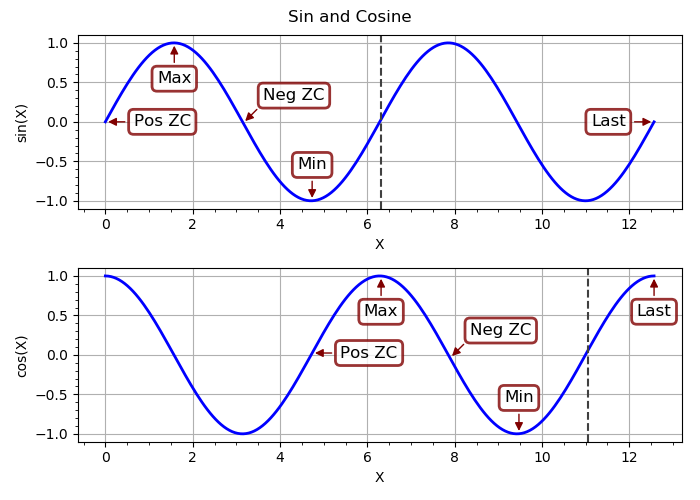

First we add a global annotation to the overall Matplotlib-manager

object pt that affects all subplots; the last point plotted is

labeled “Last.” Then we enter the context manager and, via the

contextualized object p, add annotations to each subplot for a

positive zero crossing. The annotations are a maximum, a negative zero

crossing, and a minimum. Here’s the result:

Note how the annotation boxes are positioned so that they don’t cover

up the plots or each other, or trespass on the borders. A surprisingly

large amount of thought and computation went into making that

happen. If you’re interested, you can check out the gory

details

of the Annotator class and its Sizer, RectangleRegion, and

PositionEvaluator helpers. (This module is also, I submit, a fine

example of the elegance and power of object-oriented programming.)

A couple of other things you might notice: There’s a dashed vertical

line at the zero crossing after the last annotation. That was added by

calling p.set_axvline(k). Take a look at the methods of

OptsBase to see

all the options you can set. Another one that the example code has set

(on a global scale, before entering the context manager) was the title

for all subplots. You could just as easily set a different title for

each subplot inside the context manager.

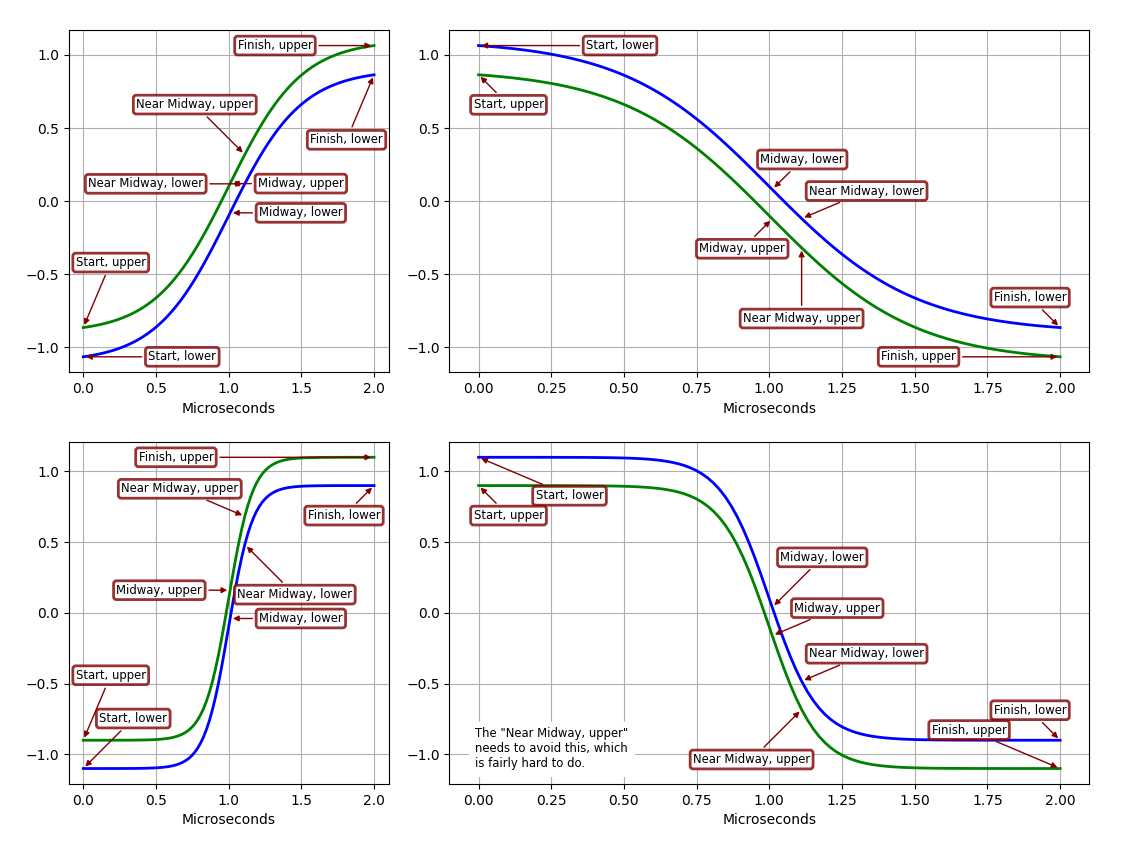

A Complex Example

Here is a more complex example of an annotated plot, with four different-sized subplots. The curves and annotations were chosen to illustrate how yampex rises to the challenge of figuring out where to put the annotation text boxes without having them overlap either of the plotted lines, the subplot borders, or each other.

There’s a lot going on here. Click on the plot for a high-definition version and you can appreciate all the details. Imagine how your plots will look, and how much easier it will be to generate them in your own Python code! I wrote yampex for my own use, and will probably never produce Matplotlib plots without it.

Running the Examples

After installing yampex with pip install yampex, you should have a

new command added to your path, yampex-examples. You can just run

that from the shell as a regular user and it will generate a

subdirectory ~/yampex-examples with some example files that can be

run to generate plots. For example, you can generate the plot by

typing ./annotate.py in a shell from that subdirectory. Take a look

at how small that file is. Here’s all the Python it contains:

import numpy as np

from yampex import plot, annotate

from yampex.util import sub

class Figure(object):

verbose = False

multipliers = (1, 3)

def __init__(self):

# DEBUG: Set True to see positioning rectangles

if self.verbose:

annotate.Annotator.verbose = True

self.p = plot.Plotter(

2*len(self.multipliers),

verbose=self.verbose, width=1500, height=1000, w2=1)

self.p.use_timex()

self.p.use_grid()

def add_annotations(self, k, prefix):

for kVector in (0, 1):

text = sub("{}, {}", prefix, "upper" if kVector else "lower")

self.sp.add_annotation(k, text, kVector=kVector)

def plot(self):

def tb(text):

self.sp.add_textBox('SW', text)

X = np.linspace(0, 2e-6, 100)

with self.p as self.sp:

for m in self.multipliers:

Y = np.tanh(m*2e6*(X-1e-6))

for sign in (+1, -1):

self.add_annotations(0, "Start")

self.add_annotations(50, "Midway")

self.add_annotations(55, "Near Midway")

self.add_annotations(99, "Finish")

if self.sp.Nsp == 3:

tb("The \"Near Midway, upper\"")

tb("needs to avoid this, which")

tb("is fairly hard to do.")

self.sp(X, sign*(Y-0.1), sign*(Y+0.1))

self.p.show()

def run():

# Plot the curves

Figure().plot()

if __name__ == '__main__':

run()

That’s it!

You can modify any of these example files to learn how to use

yampex, and your modifications will not be overwritten if you run

yampex-examples again. To get the original example file, just delete

the modified one and run yampex-examples, and the original will be

copied.

The simplest example of all is to try out the package-level xy

function. You can do that without installing any other examples. It

provides ultra-simple XY plotting of a numerical sequence or Numpy

vector, or a pair of Numpy vectors. Here is all you have to do in

ipython or the Python console to try it:

In [1]: from yampex import xy In [2]: xy([0,1,2,1,0,-1,-2,-1,0])

With these two lines you get a sawtooth waveform. It’s a very handy little function when you’re trying to get a quick visualization of vectors in Python. If you want to plot to equal-length vectors against each other, just include them both as arguments.

Happy plotting!

License

Copyright (C) 2017-2021 by Edwin A. Suominen, http://edsuom.com/:

See edsuom.com for API documentation as well as information about Ed's background and other projects, software and otherwise. Licensed under the Apache License, Version 2.0 (the "License"); you may not use this file except in compliance with the License. You may obtain a copy of the License at http://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0 Unless required by applicable law or agreed to in writing, software distributed under the License is distributed on an "AS IS" BASIS, WITHOUT WARRANTIES OR CONDITIONS OF ANY KIND, either express or implied. See the License for the specific language governing permissions and limitations under the License.

Notes

-

You can also supply a single vector with just one argument. Then that vector will be plotted with the vector integer indices as the x-axis. ←